When Men Weaponize Scripture...

... Reflections on Haq and the Shah Bano Case

When Men Weaponize Scripture: Reflections on Haq and the Shah Bano Case

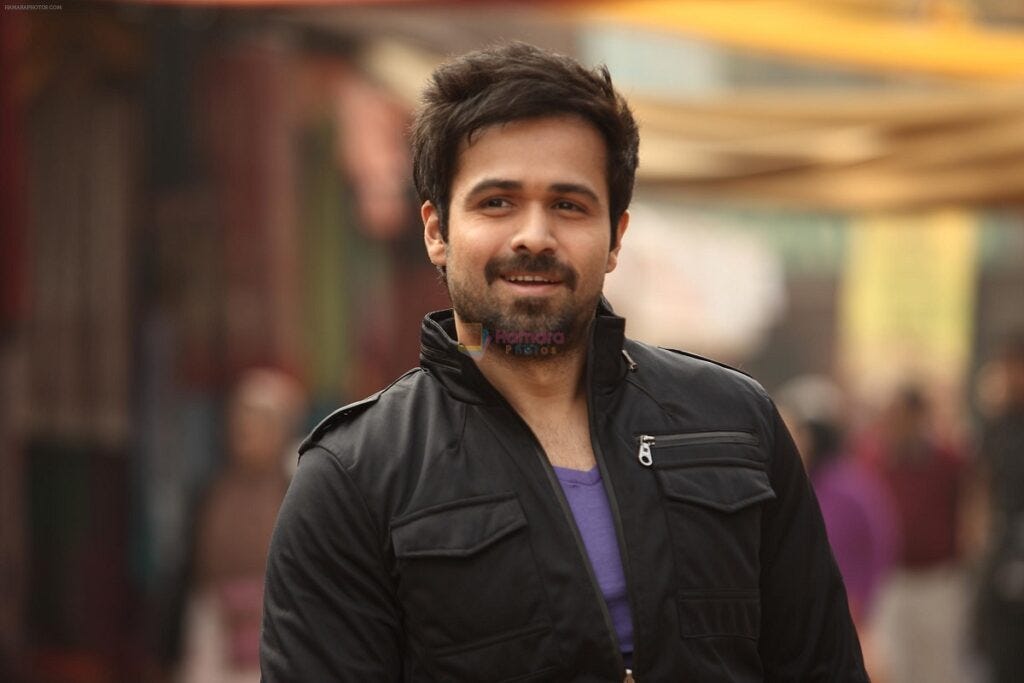

I do not watch films often. My relationship with cinema has become increasingly transactional over the years. I emerge from my self-imposed big-screen hiatus only when a story speaks to the larger maladies plaguing Muslim society, when narrative transcends entertainment to become a necessary witness. Haq was such a film. After nearly three years without bothering about a movie, I sat down to watch Yami Gautam Dhar and Emraan Hashmi navigate the courtroom drama inspired by Shah Bano’s fight for dignity in 1980s India.

The film arrived during a moment when I found myself wrestling with questions that refuse easy answers. How do we reconcile our faith with the countless ways it gets twisted to serve power? When does interpretation become weaponization? And what do we do when the men claiming to protect Islam are actually the ones violating its spirit?

Haq forced me into research that I did not want to conduct, down rabbit holes of legal precedent and theological debate, which left me angry and exhausted. The truth about Shah Bano’s case is worse than fiction; about how Islamic law has been manipulated to deny women their God-given rights is a wound that still festers.

The Man Who Chose Pride Over Provision

Shah Bano was 62 years old in 1978 when her husband of 69 years, Mohammad Ahmed Khan, threw her out of their home. A successful lawyer in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, Khan had taken a second wife and decided he no longer needed his first family. He divorced Shah Bano through triple talaq and stopped all financial support.

Let that sink in. A woman who had borne him five children, who had devoted nearly half a century to building a life with this man, was discarded like defective property. When Shah Bano approached the courts seeking maintenance, Khan’s response demonstrated the depth of his contempt. He initially agreed to pay 200 rupees (worth 2,493.67 rupees today when adjusted for inflation, approx N40,000) monthly for their children. When ordered by a magistrate to pay Rs. 25 per month for his ex-wife, he fought the ruling all the way to the Supreme Court of India.

Later, the High Court of Madhya Pradesh increased the amount to Rs. 179.20 monthly, but Khan could not accept this indignity, and this was not because he lacked resources. The man was a thriving advocate, but because ego mattered more than obligation, because patriarchy teaches men that admitting responsibility to a woman constitutes emasculation.

The film Haq captures this toxic dynamic with devastating clarity. Emraan Hashmi’s Abbas Khan (the fictionalized version) is not portrayed as a cartoonish villain but as charming and educated. He also quotes scripture fluently while performing piety convincingly, but beneath that polished exterior lies the rot of entitlement that Islam came to dismantle.

What disturbed me most while watching Haq was recognizing Abbas Khan not as an outlier, but as an archetype. I have met this type of man in Lagos and other major cities in Nigeria. He is the brother who inherits everything because daughters are considered temporary members of the family. He is the husband who controls every financial decision while quoting “men are the protectors of women” without understanding what protection actually means. He is the father who forbids his daughter’s education because of a twisted interpretation of purdah.

When Scripture Becomes a Weapon

The Quran is explicit about financial maintenance. In Surah At-Talaq (65:6), Allah commands: “Lodge them where you dwell, according to your means, and do not harm them in order to oppress them.” The verse continues with instructions for pregnant divorced women, but establishes the principle clearly. Do not use deprivation as punishment.

Surah Al-Baqarah (2:241) states: “For divorced women, maintenance should be provided on a reasonable scale. This is a duty on the righteous.” The word used is mataa’un bil-ma’roof, provision according to what is fair and customary. Not charity but duty (haqq).

When Shah Bano’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1985, a five-judge bench led by Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud delivered a landmark judgment. The Court ruled that Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which mandates maintenance for destitute ex-wives regardless of religion, applied to Muslims as well. The Court went further, examining Islamic sources directly. Chief Justice Chandrachud wrote: “There is no conflict between the provisions of Section 125 and those of the Muslim Personal Law on the question of the Muslim husband’s obligation to provide maintenance for a divorced wife who is unable to maintain herself.”

The judgment quoted extensively from the Quran and scholarly interpretations, concluding that Islamic law itself requires maintenance beyond the iddat period (the three-month waiting period after divorce) if a woman cannot support herself. The Court observed that the true spirit of the Quran promotes compassion and justice, not abandonment.

Muslim organizations erupted. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, and other religious bodies joined Khan’s appeal as intervenors. They framed the Supreme Court’s decision as an attack on Muslim Personal Law, an encroachment by secular authority into religious territory. Massive protests followed. Muslims took to the streets, insisting their faith was under siege.

But here is what infuriates me. Where in the Quran does Allah permit a man to throw his elderly wife into destitution? Where in the Hadith did the Prophet (peace be upon him) model this cruelty? When Hind bint Utbah complained to the Prophet about her husband Abu Sufyan’s stinginess, the Prophet’s response was clear: “Take what is sufficient for you and your children according to what is customary” (Sahih Bukhari). The Prophet authorized a wife to take from her husband’s wealth if he refused to provide adequately. He did not tell her to accept deprivation as a religious duty.

The Prophet said: “The most perfect of believers in faith are those who are best in character, and the best among you are those who are best to their wives” (Tirmidhi). Mohammad Ahmed Khan, in refusing to pay Rs. 179.20 per month to the mother of his five children was violating Islamic tenets, and the clerics who rallied to his defense were complicit in that violation.

The Political Betrayal

What happened next remains one of the most shameful chapters in modern Indian history. The Congress Party, led by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, had won a landslide victory in 1984, and facing pressure from Muslim political leaders who claimed their vote bank would abandon the party if the Shah Bano judgment stood, Gandhi capitulated.

In 1986, the Indian Parliament passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, which effectively nullified the Supreme Court’s judgment. The Act restricted maintenance for divorced Muslim women to the iddat period only, enshrining exactly what the Supreme Court had ruled against. The law declared that after three months, a divorced woman’s relatives were responsible for her and her children’s upkeep, and if she had no relatives, the State Wakf Board would provide for her and her children.

Arif Mohammad Khan, then a Minister in Rajiv Gandhi’s government, resigned in protest. He had defended the Supreme Court judgment passionately in Parliament, arguing that it aligned perfectly with Islamic principles. When Gandhi reversed course, Khan refused to remain complicit. He walked out of the Cabinet and eventually left the Congress Party entirely. In interviews, Khan described the intense pressure Gandhi faced from clerics and how political expediency triumphed over principle.

Shah Bano herself, now 70 years old and exhausted by years of legal battle, eventually issued a statement renouncing the Supreme Court judgment. Under immense community pressure and reportedly influenced by her children, who faced ostracization, she claimed she had been misled by lawyers and that Islamic law was sufficient. The woman who had fought for seven years surrendered.

But the law she fought for did not die with her surrender. In subsequent cases, particularly Danial Latifi v. Union of India (2001), the Supreme Court interpreted the 1986 Act in a manner that preserved the essential protections of the Shah Bano judgment. The Court ruled that a husband must make “reasonable and fair provision” for his divorced wife during the iddat period itself, which should be sufficient for her lifetime maintenance. This creative interpretation effectively restored what Parliament had tried to take away.

The Father Who Understood Protection

One of Haq‘s most powerful elements is the portrayal of Shazia’s father, Maulvi Basheer Anwer, played by Danish Husain. Here was a man who understood what the term “protector” (qawwam) actually means in the Islamic context. When the entire village turned against his daughter for daring to take her husband to court, when clerics condemned her for defying Muslim Personal Law, and when neighbors stopped speaking to the family, Maulvi Anwer stood firm.

This man was a teacher, responsible for educating the village’s children. His reputation was everything, yet he chose his daughter’s dignity over social acceptance. He chose justice over reputation. He chose the spirit of Islam over the letter being weaponized against women.

The Quran uses the word qawwam in Surah An-Nisa (4:34): “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given some of them an advantage over others, and because they spend of their wealth.” The verse is among the most misunderstood and misused in the entire Quran. Male translators and interpreters have rendered qawwam as giving men authority over women, a carte blanche for dominance. But qawwam derives from the root word meaning “to stand firm,” “to take care of,” “to be responsible for.” It describes function, not superiority.

Protection means ensuring safety, providing for needs, and defending against harm. Maulvi Anwer understood this. Mohammad Ahmed Khan did not, and therein lies the chasm between men who embody Islamic values and men who merely perform them.

The film shows how the village ostracized not just Shazia but her entire family. Children stopped coming to Maulvi Anwer’s school. Families that had respected him for decades suddenly questioned his understanding of Islam. How could a teacher of religion support his daughter’s rebellion against God’s law?

But Maulvi Anwer recognized what they could not. That Shazia was not rebelling against Islam but appealing to it. She was asking the courts to acknowledge what the Quran already guaranteed: that a woman abandoned by her husband, left destitute with children to raise, has a right to support. That justice transcends convenience.

This dynamic repeats across cultures. Patriarchy weaponizes religion, then punishes women who refuse to accept their own oppression as a divine mandate. Also, the men who stand with women often get ostracized too because patriarchy cannot tolerate male defectors. “They undermine the entire system.”

The Financial Abuse We Normalize

Let us talk about the money because money matters. Mohammad Ahmed Khan fought a seven-year legal battle, spending vastly more on lawyers and court fees than he would have spent simply paying the maintenance ordered. The amounts in question were never substantial. Rs. 25 per month initially. Rs. 179.20 after the High Court ruling. Even adjusted for inflation, these were modest sums for a successful lawyer.

But it was never about the money, but control. It was about ensuring that Shah Bano, having dared to assert her legal rights, would be taught a lesson. That other Muslim women watching her case would understand the cost of defiance.

Financial abuse is among the most insidious forms of domestic violence because it is rarely recognized as violence at all. When a husband controls every rupee or naira, when a wife must beg for grocery money, when children’s school fees become negotiating tools, we call this “family dynamics.” We frame it as the natural order, as men exercising their God-given authority to manage household finances.

But the Prophet (peace be upon him) established women’s financial independence repeatedly. When he married Khadijah, he did not take control of her wealth. She remained a successful merchant. When Fatima complained about the physical toll of housework, the Prophet did not tell her that suffering was her wifely duty. He acknowledged her struggle and suggested different solutions.

Islamic law guarantees women the right to earn and maintain separate finances from their husbands. The mahr (dowry) a woman receives at marriage belongs to her exclusively. The inheritance she receives from her parents is hers alone, and the maintenance (nafaqah) her husband owes her is not a favor but a legal obligation.

Yet somehow, across the Muslim world, women’s economic dependence on men has become the Islamic model. Fathers control daughters. Husbands control wives. Sons control elderly mothers, and when women try to access their Islamic rights, they are accused of destroying the family unit, of importing Western feminism, and of lacking patience and submission.

When Patriarchy Dresses as Piety

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board’s intervention in Shah Bano’s case revealed the fundamental problem. These men, claiming to protect Islamic law from secular encroachment, actually protected male privilege from divine justice. They read the Quran through centuries of patriarchal interpretation, then declared their reading the only legitimate one.

Take Surah Al-Baqarah (2:228), which states: “Women have rights similar to those of men over them in kindness, and men are a degree above them.” Traditional interpretations have seized on “a degree above” to justify male superiority across all domains, but the verse explicitly states women have rights “similar to” men’s rights, and the “degree” is explained by many scholars, including Muhammad Asad, as referring to men’s financial responsibility, not ontological superiority. The degree of additional responsibility corresponds to the degree of economic obligation. The rights and responsibilities balance.

But patriarchy does not traffic in balance. It needs hierarchy. So it takes verses about specific responsibilities and transmutes them into blanket authorization for male dominance. It reads temporary historical contexts as permanent divine commands. It quotes half-verses while ignoring qualifying clauses.

When Mohammad Ahmed Khan’s lawyers argued before the Supreme Court, they claimed that Islamic law required him to provide for Shah Bano only during the iddat period. They cited selective interpretations while ignoring Quranic verses about providing for divorced women “on a reasonable scale” (2:241) and the prophetic tradition of extending support beyond the minimum legal requirement.

The Supreme Court examined these claims and found them wanting. Chief Justice Chandrachud wrote: “It is a matter of great regret that some of the texts of the Holy Quran, of the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, and of the commentaries of eminent jurists on the Quran, were brought to our notice for the first time during the hearing of these appeals, though the issue involved has been pending before courts for quite some time.” He was noting, diplomatically, that Muslim organizations had hidden the very Islamic sources that supported Shah Bano’s claim.

This is how patriarchy operates. It weaponizes scripture selectively, presenting convenient interpretations as divine mandate while suppressing inconvenient evidence and when confronted, it accuses critics of attacking religion rather than defending its misuse.

The Cost of Courage

Haq ends with the Supreme Court ruling in Shazia Bano’s favor, a moment of vindication that the real Shah Bano experienced in 1985. But the film includes title cards acknowledging what happened next: the government’s betrayal through the 1986 Act, and eventually, the 2019 criminalization of instant triple talaq under the Narendra Modi government.

These epilogues complicate the narrative. The BJP government’s 2019 law and the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act criminalized instant triple talaq, fulfilling a decades-old demand of Muslim women’s rights groups. But the law also served the BJP’s broader political project of portraying Muslims as backward and oppressive, requiring Hindu nationalist intervention.

This creates an impossible position for Muslim women. When they fight for their Islamic rights against patriarchal interpretations, they risk being weaponized by Islamophobic forces that care nothing about their actual well-being. When they stay silent to avoid giving ammunition to anti-Muslim bigotry, they suffer under systems that violate their dignity.

Shah Bano paid an enormous price for her courage. Years of litigation, community ostracization, family pressure, and finally, a forced renunciation of the very judgment she had won. Her children faced stigma. Her name became synonymous with controversy, and the men who destroyed her life in the name of Islam, who turned religious law into a tool of cruelty, faced no accountability whatsoever.

Siddiqua Begum, Shah Bano’s daughter, issued a legal notice in October 2025 against the makers of Haq, claiming the film drew from her mother’s case without consent. The notice reveals the ongoing trauma, the ways this battle continues reverberating through generations. Shah Bano is gone, but her children still bear the weight of her fight.

What Redemption Looks Like

I finished the movie thinking about Maulvi Anwer, Shazia’s fictional father, who understood that protecting your daughter means standing with her even when the entire community turns against you. I thought about Arif Mohammad Khan, who sacrificed his political career rather than endorse injustice. I thought about the women across India who watched Shah Bano’s case and found the courage to demand their own rights.

Islam came to liberate. “There is no compulsion in religion” (Quran 2:256). The religion that abolished the burial of infant daughters, that gave women inheritance rights thirteen centuries before European women gained them, that made women’s consent mandatory for marriage, was never meant to become a prison.

But somewhere along the journey, men reinterpreted revelation to serve power. They took a faith that centered justice (adl) and compassion (rahma) and transformed it into a system that prioritizes male authority and female submission. They quoted scripture while violating its spirit, and they convinced generations of Muslims that oppressing women in the name of God was piety.

The Shah Bano case exposed this contradiction. A 62-year-old woman asking for Rs. 179.20 per month to survive became a national crisis because acknowledging her rights threatened an entire edifice of patriarchal interpretation. The system could not accommodate her simple demand for dignity without collapsing.

And perhaps that is precisely why we need more Shah Banos. More women who refuse to accept that abandonment is Islamic. More women who appeal to the Quran’s justice against the clerics’ cruelty. More women who understand that fighting for their rights does not make them a bad Muslim. It makes you a believer who trusts that Allah is not the author of your oppression.

The Quran ends Surah Al-Baqarah’s divorce verses with: “These are the limits set by Allah. Do not transgress them, for whoever transgresses Allah’s limits, they are the wrongdoers” (2:229). Mohammad Ahmed Khan transgressed. The clerics who supported him also transgressed.

The Question That Remains

Writing this essay, I return to the question I started with. How do I separate my faith from the countless ways it gets weaponized? How do I remain Muslim when so many Muslims defend the indefensible in Islam’s name?

The answer, I think, lies in the distinction between Islam as divine revelation and Islam as patriarchal tradition. The Quran is a revelation, but centuries of jurisprudential interpretation, of cultural practice dressed as religious mandate, and of male scholars declaring their opinions binding on all believers, had muddled the waters.

When I read that men are women’s protectors, I can choose the patriarchal reading that grants me authority. Or I can choose the reading that obligates me to ensure well-being, to provide for needs, to defend dignity even at personal cost. When I read about divorce regulations, I can weaponize them to abandon responsibility. Or I can recognize them as minimums, not ideals, and extend grace beyond what the law requires.

Haq is not a perfect film. Reviews note its tendency toward melodrama and its occasionally heavy-handed treatment of complex issues. But it succeeds in humanizing what too often gets reduced to legal abstraction. Yami Gautam Dhar’s performance captures Shah Bano’s exhaustion, her confusion at being punished for asserting basic rights, and her desperate need to be seen as a person rather than a problem.

And perhaps that is what we need. Not more sophisticated theological arguments. Not more legal precedents. But more stories that remind us that behind every Fatwa and every religious interpretation are human beings whose lives hang in the balance.

Shah Bano Begum died in 1992 at age 76. She spent her final years in obscurity, having renounced the judgment that bore her name. The Supreme Court victory meant nothing in the face of community rejection. The law changed nothing for her personally.

But the judgment remains. And women continue fighting. Slowly. Painfully. Nonetheless, Muslim societies are being forced to reckon with the gap between Islam’s promise of justice and Muslim men’s practice of oppression.

Haq means both “right” and “truth” in Arabic. Shah Bano had a right. She spoke the truth, and somewhere, in the space between what we claim to believe and how we actually live, Islam waits to be redeemed.

While I was watching the movie, I kept on saying that I can't wait to write a review on it. Seeing this gladdens my heart and I am happier that it came from a man otherwise they would have said the woman is a feminist. Thank you so much for this. May Allah honor you.

Oh my God.

I can't say thank you enough for capturing this beautifully. I remember being very angry when I watched this movie and you've done great justice.

One thing I would humbly request is how Bank religious grounding made it easy for her to ask for her right. She mentioned she's not westerly educated but when it comes to islamic education. She knows more. More women should study their religion. That alone gave Bano courage.