Rediscovering Nuance in the Debate over Women in Islam...

... How Hadia Mubarak Analyses Classical Tafsīr for Modern Conversations on Gender

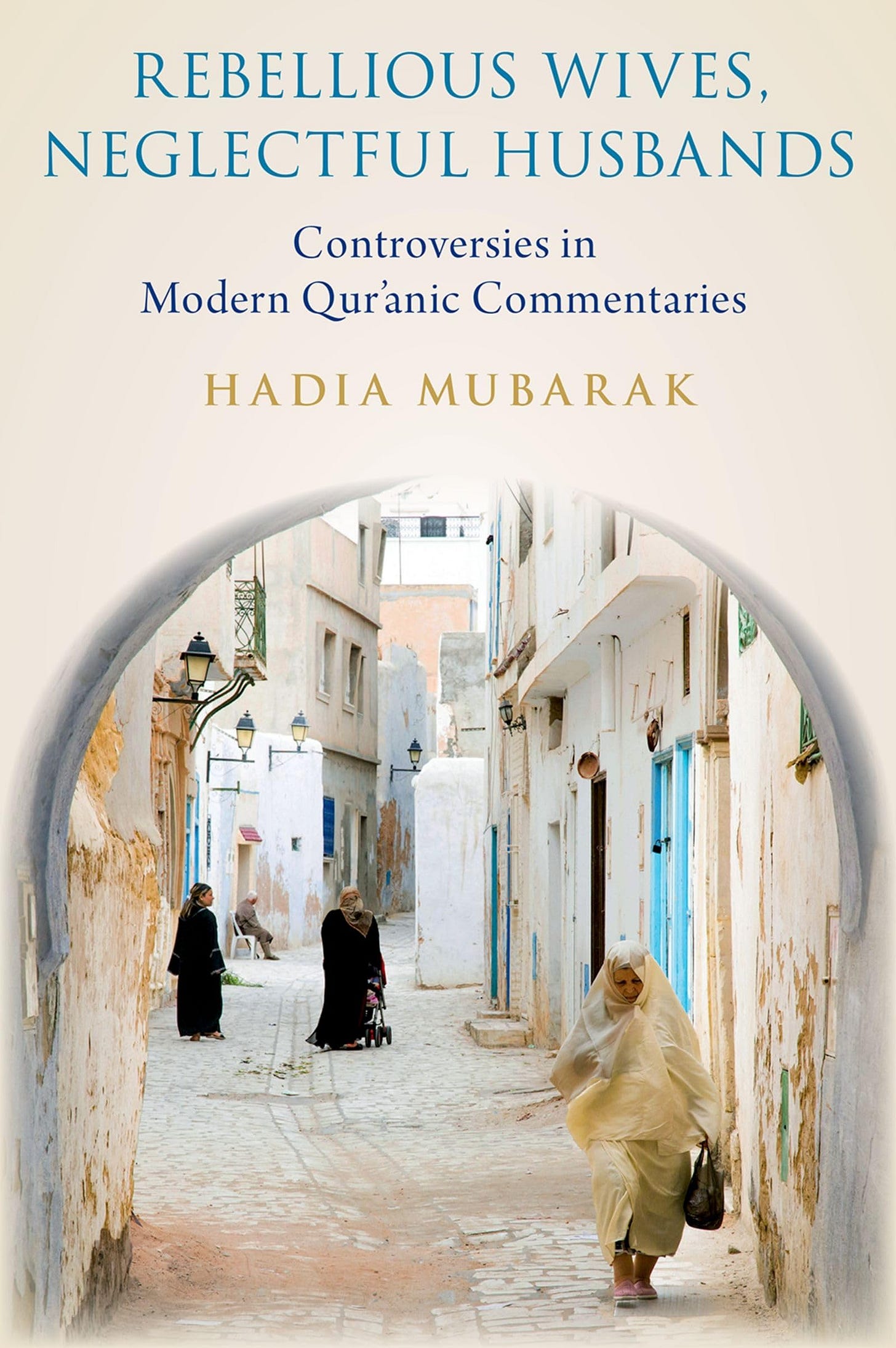

I’ll admit it: I’ve never fallen so obsessively in love with a work of academic non-fiction as I have with Hadia Mubarak’s Rebellious Wives, Neglectful Husbands. You might already know my disdain for what I call “progressive Muslamic academia.” In my opinion, it is an oft-tendentious scholarship that often caricatures classical tafsīr (Qur’anic exegesis) as monolithically misogynistic. Their arguments sometimes require barely two brain cells to spot as intellectually dishonest. I rage in private. But Mubarak wins you over with scholarly grace.

She enters the arena with precision and courtesy, delivering a sustained critique of both premodern and modern commentators (mufassirūn) on four Qur’anic verses: 2:228 (marital hierarchy), 4:3 (polygyny), 4:34 (“rebellious wives”), and 4:128 (“neglectful husbands”).

These verses have fueled endless debates about Islam and gender. By drawing on exegetes from al-Ṭabarī (d. 923) to Ibn ‘Ashūr (d. 1973), Muhammad ‘Abduh (d. 1905) to Sayyid Quṭb (d. 1966), she builds a bridge across time, showing that these debates are anything but static and that dismissing the entire tradition as uniformly patriarchal is simply lazy.

Why This Book Matters

At first glance, Mubarak’s project might sound niche. You might think this is another lengthy book about gendered verses in modern commentaries. But it strikes at the heart of a larger crisis: the polarization between “classicalist” and “progressive” approaches to Islam. On one side, you have scholars who treat the tafsīr tradition as an archaic fossil fuel: useful for tradition, but morally suspect when it comes to women. On the other hand, you have those who sacralize modern feminist readings so utterly that they dismiss centuries of scholarship without engaging its methodology.

Mubarak refuses both extremes. She illustrates that the exegetical tradition is complex, contingent, and evolving. That it is neither monolithically patriarchal nor unflinchingly egalitarian. Her careful, rule-governed study of tafsīr disarms the caricatures on both sides.

She insists that real engagement with the Qur’an’s gendered passages demands an understanding of the process of tafsīr. Its hermeneutical principles and philological methods, not just a desire to impose a political agenda.

By situating her analysis against the backdrop of Western colonial critiques and 20th-century reformist currents in Egypt and Tunisia, Mubarak reminds us that Muslim scholars themselves have long grappled with questions of modernity, justice, and women’s rights. And often, with surprising nuance, they diverge from the neat binaries that dominate contemporary discourse.

Tradition Meets Modernity: The Four Exegetes

Central to Mubarak’s study are four 20th-century mufassirūn whose works embody distinct intellectual currents:

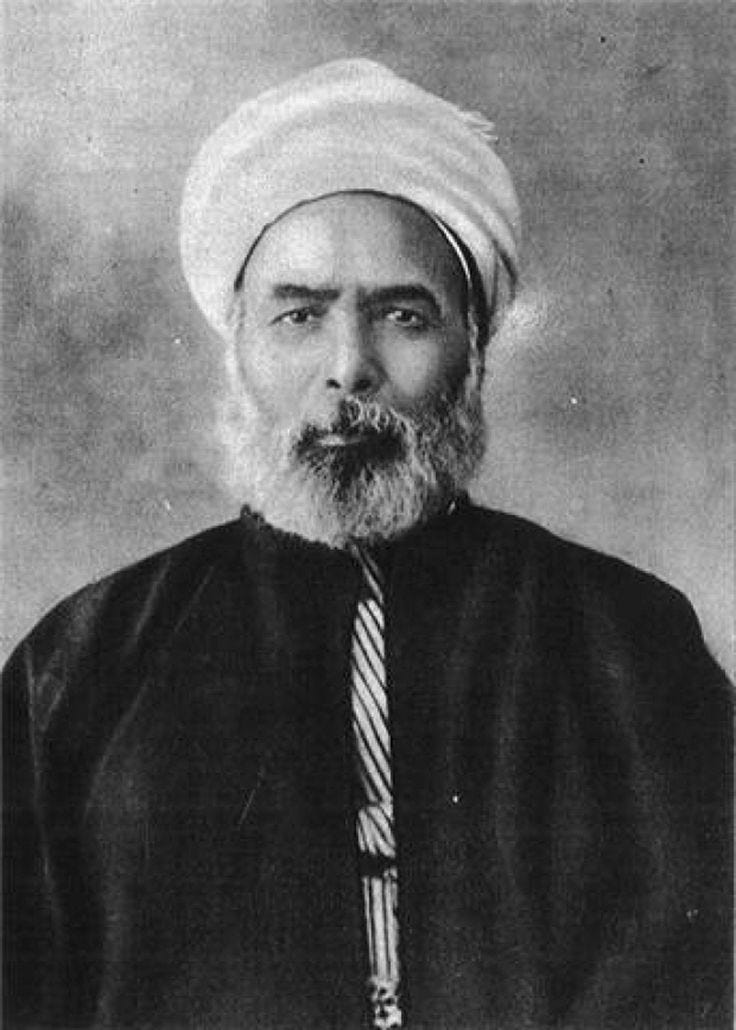

Muhammad ‘Abduh (1849–1905): The pioneering Islamic modernist, who sought to reconcile reason and revelation, championing a rational hermeneutic without severing ties to tradition.

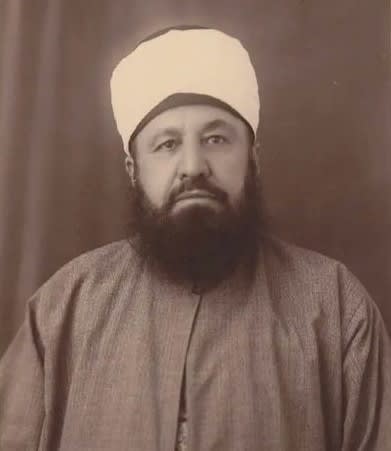

Rashīd Riḍā (1865–1935): ‘Abduh’s disciple and a founder of modernist Salafism, blending reformist zeal with a call to return to the pristine sources.

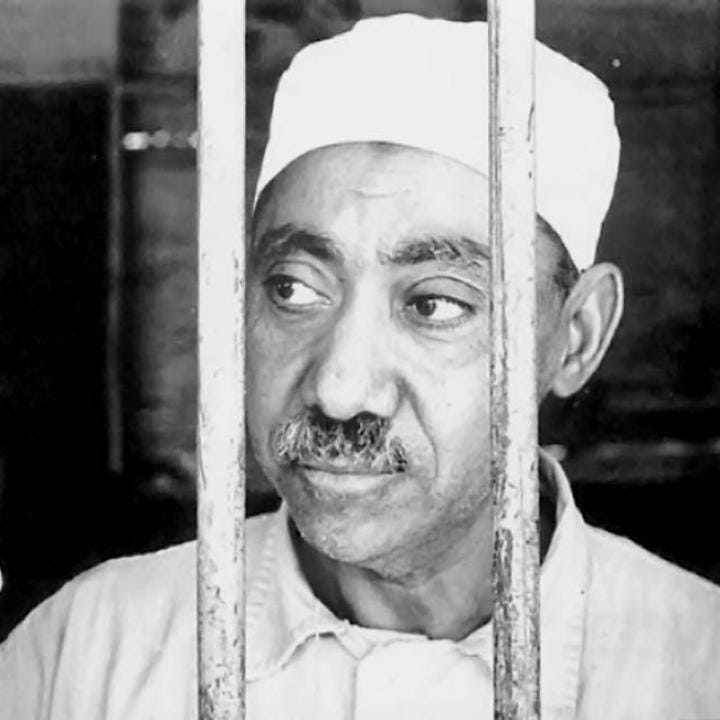

Sayyid Quṭb (1906–1966): The Islamist ideologue whose Fi Ẓilāl al-Qur’ān reframed the Qur’an as a manual for lived revolution, a commentary more journalistic and rhetorical than classical exegesis.

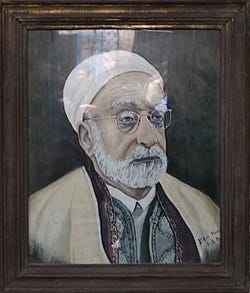

Muḥammad al-Ṭāhir Ibn ‘Ashūr (1879–1973): The jurist-exegete of Al-Taḥrīr wa’l-Tanwīr, who represents a “pluralistic and evolving notion of tradition,” merging philological rigor with an openness to modern concerns without succumbing to reductionism.

By pairing these modern voices with seven premodern tafsīr luminaries (al-Ṭabarī, al-Rāzī, al-Zamakhsharī, al-Qurṭubī, al-Bayḍāwī, Ibn Kathīr, and others), Mubarak creates a rich mosaic that reveals how each generation contends with its own colonial, intellectual, and political challenges.

The Four Verses: Flashpoints of Gender Debate

1. Surah 4:34: “Rebellious Wives” (Nushūz al-Mar’ah)

This is perhaps the most contested verse in modern feminist readings of the Qur’an. Mubarak demonstrates that classical exegetes offered diverse understandings of “nushūz” (rebellion) and the prescribed remedies, ranging from patting one’s wife to more severe measures. Far from unanimous, their opinions reflected rigorous debates about marriage, social order, and the underlying ethical principles in the text. When 20th-century mufassirūn revisited 4:34, they did so with an acute awareness of colonial critiques of Islam’s “misogyny,” yet each arrived at distinct stances: ‘Abduh urging a spirit-of-justice approach, Quṭb reframing it as a safeguard of dignity, and Ibn ‘Ashūr insisting on a strict philological reading.

2. Surah 4:128: “Neglectful Husbands” (Nushūz al-Rajul)

Less famous than 4:34 but equally revealing, 4:128 addresses situations where a wife fears opposition from her husband. Mubarak shows how exegetes from al-Ṭabarī to Ibn Kathīr explored questions of khul‘ (mutual divorce) and the balance of rights. Modern mufassirūn seized on 4:128 to explain women’s agency within marriage, with Quṭb’s commentary offering one of the most progressive readings, arguing that the verse demonstrates the Qur’an’s inherent concern for women’s welfare.

3. Surah 4:3: Polygyny

Often invoked as evidence of male privilege, 4:3 permits polygyny “if you fear you cannot treat orphans fairly.” Here, Mubarak dissects centuries of commentary on justice (“‘adl”) and the verse’s conditional permissiveness. Rashīd Riḍā and Quṭb, for example, emphasized the verse’s restrictive tone, effectively discouraging polygyny by foregrounding the ethical bar of absolute justice. Ibn ‘Ashūr, meanwhile, distinguished normative permission from moral recommendation, urging readers to regard the verse in light of maqāṣid (objectives) of Shariah, which is, protection of the vulnerable.

4. Surah 2:228: Marital Hierarchy (“Degree of Superiority”)

Ibn Kathīr’s oft-cited “men have a degree over women” line has fueled wholesale condemnation of classical tafsīr as inherently “misogynistic.” But Mubarak shows that al-Bayḍāwī and al-Qurṭubī, for instance, read “darajah” in the context of financial duties and divorce, not an ontological hierarchy. Ibn ‘Ashūr went further: he argued that “degree” refers to the male’s role as protector, not moral or spiritual superiority. Even Quṭb, writing in the heat of anti-colonial struggle, interpreted the verse in a way that uplifted women’s post-divorce rights.

The Big Three Questions

Mubarak’s book pivots on three fundamental inquiries:

Is the Qur’an a patriarchal monolith? She shows that, far from an unbreakable patriarchal chain, the exegetical tradition reflects polyvalent meanings shaped by context and method.

How do modern exegetes’ own positionalities influence their readings? Every commentator, ‘Abduh, Riḍā, Quṭb, Ibn ‘Ashūr, brings personal, ideological commitments to the text. Mubarak encourages us to read for both exegesis (tafsīr) and eisegesis (importing one’s own biases).

How have commentators innovated while remaining anchored to tradition? Contrary to both the ‘rupture-mania’ of some modernists and the ‘continuity-fetish’ of some conservatives, Mubarak highlights a “pluralistic and evolving notion of tradition.” Exegetes recalibrate old opinions, reject certain inherited views, and propose new insights, all within the parameters of a rule-governed tafsīr discipline.

Humanizing the Debate

One of the book’s greatest strengths is the humanity with which Mubarak portrays her subjects. Rather than depicting her mufassirūn as ivory-tower giants, she shows them wrestling with moral dilemmas, political crises, and personal convictions:

Abduh, torn between colonial pressures and a faith that demanded justice, strives to make the Qur’an speak to the educated layperson.

Riḍā, impassioned yet cautious, tries to revive the golden age’s spirit without lapsing into anachronism.

Quṭb, furious with Western imperialism, channels his anger into a revolutionary tafsīr that still finds empathetic readings of women’s verses.

Ibn ‘Ashūr, the jurist-scholar, models a kind of patient rigor, neither sentimental nor cynical, seeking meaning in every lexical root.

By foregrounding their contexts, be it the aftermath of British colonial rule, the struggle for national identity, or the rise of Islamist movements, Mubarak reminds us that exegesis is not abstract philosophy but lived, embodied scholarship.

Why Tafsīr Matters for Feminist Engagement

For many Muslim women (many of whom had to resort to seeing solace in feminism), the genre of tafsīr feels like a relic. Steeped in male voices and arcane Arabic philology. They prefer thematic Qur’an study (qirā’ah mawḍū‘iyyah), cherry-picking verses under modern hermeneutics. Yet Mubarak warns that sidelining tafsīr is dangerously reductive: it robs us of the intellectual discipline that produces rigorous, contextual, and text-grounded interpretations.

Her invitation to feminist scholars is clear: immerse yourselves in the rules of tafsīr before passing sweeping judgments. Engage with the original Arabic, the chain of narrations (isnād), the linguistic analyses (naḥw, ṣarf), and the legal-theological debates. Only then can one make credible interventions that build on, not bulldoze, the rich exegetical tradition.

Beyond Binaries: Toward Nuanced Conversation

Mubarak’s work transcends rote oppositions. Classical vs. modern, patriarchal vs. egalitarian, textual vs. contextual. She urges us to abandon “cookie-cutter” labels and binary frames:

Patriarchal vs. Egalitarian: Tafsīr has never been wholly one or the other; it has instead juggled multiple interpretive stances.

Textual vs. Thematic: Atomistic, philological tafsīr uncovers depth that thematic readings might miss; thematic hermeneutics can risk anachronism.

Tradition vs. Reform: Reform can flourish only when rooted in tradition; tradition must be dynamic enough to meet contemporary challenges.

This pluralistic ethos is perhaps Rebellious Wives, Neglectful Husbands’ most vital lesson: meaningful dialogue about Islam and women requires embracing complexity, acknowledging disagreement, and finding common ground in a shared commitment to justice.

Conclusion: A Book to Cherish

I could continue dissecting each chapter, but I’ll spare you the spoiler. Instead, let me end with the simplest praise: This book is brilliant. It must be read by scholars, activists, students, and anyone who cares about Islam’s future.

In a time when “Islam and women” is too often a battleground of slogans, Mubarak offers a refuge of nuanced scholarship. She honors the voices of her mufassirūn subjects, premodern and modern, while holding them to account. She writes not from the fury I sometimes feel, but with a poised generosity that invites readers in.

If you want to understand how Qur’anic exegesis has engaged gender across twelve centuries, or if you simply hunger for clear, humane, and fair-minded analysis, pick up Rebellious Wives, Neglectful Husbands.

It stands as the best book I’ve read this year, and perhaps this decade, on the intersection of gender, tradition, and modernity in Islam.

I should read this book

i am in utter awe at this. Never have i seen a book done such justice. i downloaded the book before i reached half of the post. This is BRILLIANT. I cant put into words how passioned i feel. how inspired i felt. how scolded i feel (good scolding!!).

Allahuma Barik!